Echoes of the Nifty-Fifty bubble

- Vertium Asset Management

- Jul 11, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 16, 2024

Quality investing, a strategy focused on companies with strong financials and consistent performance, has become a dominant force. Pioneered by academics like Novy-Marx (2013), showed that high-quality stocks with stable earnings, strong balance sheets and healthy profit margins typically outperform. This strategy gained significant traction in the investment world, with numerous exchange-traded funds (ETFs) launched to mirror the performance of quality companies. Even active fund managers have jumped on the bandwagon, rebranding themselves as quality focused.

However, quality investing is not a new concept. It is essentially an extension of "blue-chip" investing, which focuses on established companies with a history of reliable performance. While quality investing has delivered impressive results in recent decades, the stock market bubble in the early 1970s serves as a cautionary tale.

Back then, investors were enamoured with a group of blue-chip darlings, which were nicknamed the ‘Nifty Fifty’. Unlike the Dot-com bubble (early 2000s) or the Pandemic bubble (2021) which were fuelled by unprofitable companies, the Nifty Fifty were highly profitable but became dangerously overvalued.

The bubble’s genesis began in the late 1960s when the market grappled with economic turbulence. Inflation, dormant for more than a decade, soared to 6% by 1970. This, coupled with a bear market brutalised many small caps. Coming out from the downturn, investors sought stability in blue chip companies that boasted resilient earnings growth – household names like IBM, Coca-Cola, and McDonald’s.

McDonald’s was the poster child of the Nifty Fifty bubble. In five years leading up to 1972, the company boasted 38% annual earnings growth, propelling its share price to a staggering price-to-forward earnings (PE) ratio of 60x by late 1972. McDonald’s future prospects did not disappoint. Profit growth was uninterrupted at 24% per annum for the next decade – a feat even more remarkable considering the recessions of the mid-1970s and early 1980s.

McDonald’s share price and profits (1967 – 1981)

Source: FactSet, Company accounts

However, McDonald’s exceptional quality could not protect investors from the substantial valuation risk at the peak of the bubble. The share price halved within two years, and it took nearly a decade to recover. Even investment legends were not immune from the Nifty Fifty demise. The late Charlie Munger, who shaped Warren Buffet’s shift towards quality investing, had an impressive track record that was tarnished by the Nifty Fifty carnage in 1973 and 1974.

Munger Partnership performance (1962 – 1975)

Today, echoes of the Nifty-Fifty resonate. Inflation has reared its head once again, reaching a worrying 9% in 2022. The pandemic-era boom and bust cycle in small-cap stocks has made investors cautious. Additionally, looming debt refinancings of many US small companies have raised their risk profile.

With high levels of market anxiety, the market has gravitated to two themes. Some investors are chasing the artificial intelligence (AI) boom, exemplified by Nvidia explosive earnings growth.

Nvidia’s share price, EPS and PE multiple (2019 – 2024)

Source: FactSet

On the other hand, cautious investors seeking refuge from volatility are gravitating towards perceived safe havens. However, higher interest rates have dampened investor appetite for traditional defensive sectors like Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Consequently, the investment opportunities for safe havens have shrunk leading to greater demand for large cap, high-quality stocks.

With concerns about smaller companies’ earnings risk, investment flows have shifted towards large caps.

US large caps versus small caps (Dec 2018 – Jul 2024)

Source: FactSet, Vertium

Within large caps, a preference for high quality companies due to their perceived lower earnings risk is evident. Costco, a retail giant renowned for predictable financials, illustrates this. Despite its ordinary growth profile, its PE ratio has skyrocketed to a record 50x – remarkably double what it was during periods of significantly higher earnings growth two decades ago. Exponential share price movements are hallmarks of booms (such as AI) or an undiscovered gem, not established, predictable companies.

Costco’s share price, EPS and PE multiple (2002 – 2024)

Source: FactSet

Procter and Gamble, another example, the world’s largest consumer staple company that owns brands like Gillette, Oral-B and Vicks also exhibits elevated valuations. While its valuation is not as extreme as Costco, its PE ratio is hovering near its twenty-year highs.

Procter and Gamble’s share price, EPS and PE multiple (2002 – 2024)

Source: FactSet

This valuation concern extends beyond the US market. In the Australia, Commonwealth Bank (CBA), known for its superior return on equity, has a PE ratio reaching a 20 year high. This is particularly surprising given stagnant earnings growth since a decade ago. This premium valuation comes despite a structural increase in retail banking competition, eliminating any healthy earnings growth.

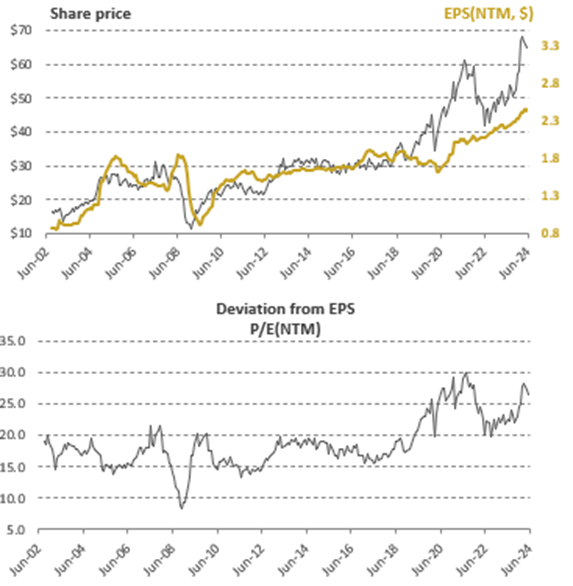

Commonwealth Bank’s share price, EPS and PE multiple (2002 – 2024)

Source: FactSet

A similar story unfolds with Wesfarmers, another prominent Australian blue-chip company, with valuation issues. Its PE ratio mirrors elevated levels observed during the pandemic market bubble in 2021.

Wesfarmers’s share price, EPS and PE multiple (2002 – 2024)

Source: FactSet

Investing in high-quality companies with attributes of strong financial strength and sustainable earnings offer undeniable merits. However, the Nifty Fifty bubble reminds us that exceptional companies can be poor investments. Today's market echoes of the past, raising concerns that some quality stocks have become disconnected from reality. Investors may unknowingly be substituting low earnings risk with high valuation risk if they buy quality at an excessive premium. If history rhymes, then ‘quality at any price’ could be as disastrous as indulging in speculative bubbles. Disciplined valuation analysis remains crucial to ensure quality translates into robust investment returns.

Reference:

Novy-Marx, R., The Other Side of Value: The Gross Profitability Premium”, Journal of Financial Economics, 108 (2013), 1 – 28.

Comments